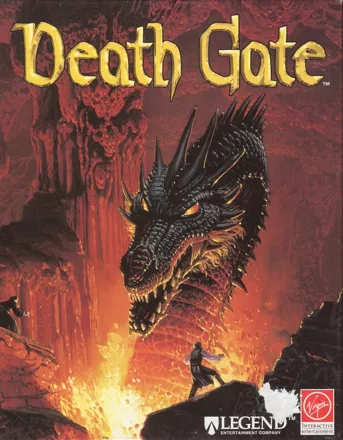

Death Gate

Description official descriptions

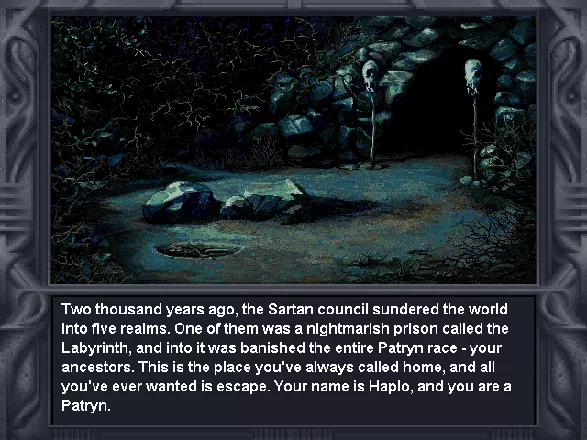

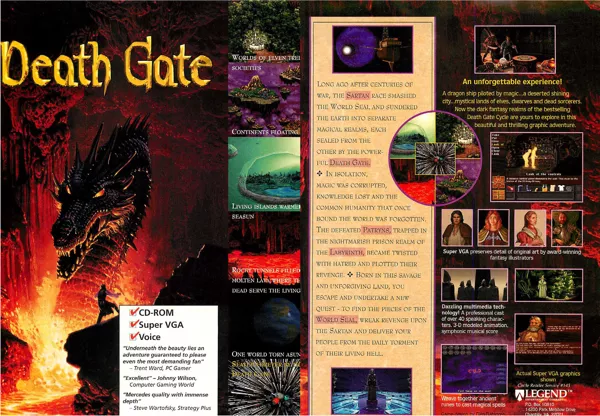

Two thousand years ago, an advanced race known as Sartan split the world into five realms. The mensch races - the humans, dwarves, and elves - were split between four of those worlds named for the four elements, and the race of Patryn was banished to the deadly Labyrinth. After those two thousand years, some of the Patryn have found their way through the Labyrinth's exit. The game's protagonist is a young Patryn named Haplo, and his mission, given to him by his lord Xar, is to sail through the Death Gate into each of the other worlds to find each world's seal piece, so that the Patryn may reconstruct the planet and have revenge on the Sartan.

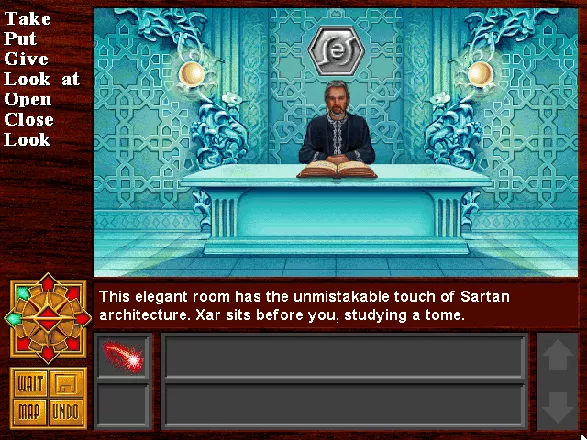

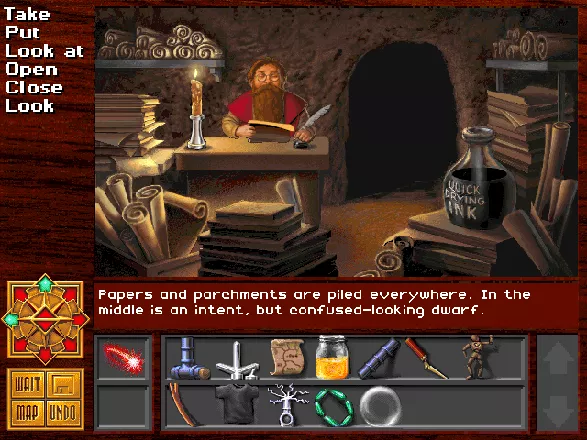

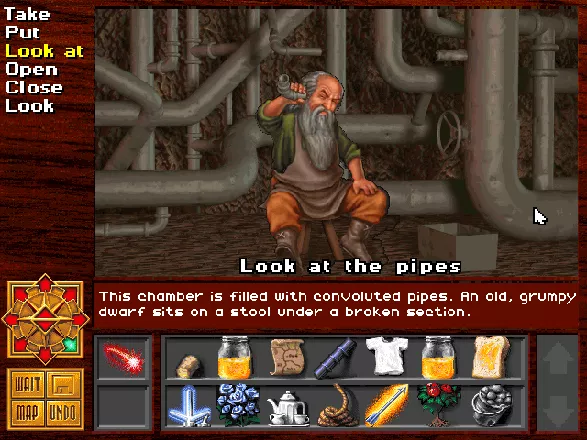

Death Gate is an adventure game that follows the tradition of interactive fiction with graphics. The entire game is viewed from first-person perspective and has plenty of text interaction through selectable verb commands, text descriptions, and dialogues with multiple choices. There are also many puzzles in the game, most of them inventory-based. A unique gameplay feature is Haplo's ability to cast magic spells, which are essential for solving many of the game's puzzles.

Groups +

Screenshots

Promos

Videos

Add Trailer or Gameplay Video +1 point

See any errors or missing info for this game?

You can submit a correction, contribute trivia, add to a game group, add a related site or alternate title.

Credits (DOS version)

57 People · View all

| Based on the novels by | |

| Design | |

| Programming | |

| System Design | |

| System Programming | |

| Graphics System | |

| Dialog System | |

| Music and Audio Direction | |

| Room Art | |

| Character Illustrations | |

| Alternate Interfaces | |

| 2-D Animation | |

| [ full credits ] | |

Reviews

Critics

Average score: 81% (based on 24 ratings)

Players

Average score: 4.2 out of 5 (based on 51 ratings with 7 reviews)

Interactive fiction at its peak

The Good

Death Gate appeared during a tumultuous epoch of game-making - the beginning of the so-called "multimedia revolution". It was also the last great era for the adventure genre. Sierra was wrapping up its famous comedy series and moving onto more mature experiments; Access Software created Under A Killing Moon; Myst conquered the masses and began to radically change the development of adventure games, for good or for (mostly) bad.

At that time, Legend had already firmly established its reputation as the leading developer of what could be considered the older sister genre of graphical adventures - interactive fiction with graphics. This sub-genre began its life as a logical descendant of text adventures. At first, some still pictures were added to the text. Then the old text input was replaced by a more user-friendly context-sensitive verb selection. This way interactive fiction became almost the same as graphical adventure; but true to the tradition, the graphics in those games were still restricted to pictures (sometimes sparsely animated) viewed from first-person perspective. And of course, text interaction was still the priority.

Text interaction is one of the strongest aspects of Death Gate. The game immerses you through the sheer wealth of interaction. Every action evokes a response from the game. You can easily lose yourself in this gameplay depth. I was amazed to see how many different responses they have written for different actions. Trying to do things was exciting; experimentation was rewarded and encouraged. Even if there were some generic messages, they were so well-written that you didn't notice they were generic. Many other adventure games of the time lazily rewarded your attempts with pitiful remarks such as "you can't do that". Well, in Death Gate, you certainly can do that. Trying different actions is so fun when you know that the game reacts to them. I don't even want to mention adventure games of later times with their lack of text and terrible "smart cursor".

Oh yes, there is plenty of text in Death Gate. That alone wouldn't count as a compliment - there is also a lot of text in Metal Gear Solid. But the text in Death Gate is good. It feels like salve on the wounds caused by the text of Japanese RPGs. From time to time you just need quality writing in games, and this one delivers. It's a pleasure to read the text descriptions. It's a pleasure to read (and hear, since they are well-voiced) the dialogues. There are emotions, there is rich vocabulary, there is humor. It's excellent writing, and it makes Death Gate similar to a book.

But it's not a book. It's an adventure game, and it shines as one. Death Gate has some of the best puzzles I've ever encountered in an adventure game, period. There is only one puzzle in the game that I found frustrating and unnecessary (rotating arrows) - but the game gives you hints for it, and even offers to solve it for you if you're stuck for too long. The rest of the puzzles follow crystal-clear logic, are given proper clues, require imagination to solve, and are perfect in difficulty. Some of the puzzles are simply brilliant and so imaginative, like for example manipulating an undead nanny who keeps reading the same children's rhyme and an undead worker who obeys every order.

One of the coolest features of Death Gate are magic spells, which you'll use to solve many of the game's puzzles. You'll usually learn those spells when somebody else uses them in front of you for his own reasons. Those spells are fascinating and guarantee a gameplay experience unlike any other adventure game around. Turning a portrait into reality, switching bodies with a dog, setting statues in motion - those are just a few examples of the interesting, creative magic of the game.

So far we have a great adventure game, but Death Gate also has something I value very much in games - it is set in a believable, rich, detailed world. In this way it reminded me of an RPG. The story comes with much background: there is plenty of historical, political, social information that you learn from dialogues with characters and from books you find in the game. I know that the world of Death Gate wasn't invented by the creators of the game (it was based on a series of novels I've never read), but the way it is shown in the game is impeccable, it's a joy to explore a world so interesting and so believable, in its own way.

The story has a certain shade of fairy tale, and is wonderful. Without any melodrama the game touches upon serious issues such as war and peace, tolerance and racism, freedom and control, and draws philosophical conclusions from them. But it never does it with annoying moralizing or overblown emotionality; it keeps the plot simple and puts all the depth into the dialogues and interaction with the characters.

The Bad

Not much. Can't say I loved the static first-person perspective. I'd certainly prefer real movement. The screens themselves are still, save for some sparse animations (like a bartender continuously wiping a glass). The graphics are good but not really "state of the art".

You can use a lot of magic spells in the game to solve its puzzles, but most of them need to be used only once or twice. Most of the time you'll have to use a spell shortly after you've learned it. The game conveniently puts you into rough spots in which the newly acquired spell is the only solution, but after the problem is eliminated, the spell in question will usually become neglected. I'd love to see more spell-based puzzles, with more creative use of those spells.

The Bottom Line

Death Gate is an exquisite game. You can fall in love with its wonderful story and its rich, detailed world, and its gameplay will intoxicate you if you like adventure games. It has marvelous interaction and some of the most delightful puzzles around. Undeniably one of the very best offerings of interactive fiction genre, Death Gate is to be savored, like a wine that only gets better with age.

DOS · by Unicorn Lynx (181780) · 2014

The Good

Unlike other adventure game (the classic quests, especially those from the house of Sierra) this game is not so "heavy". Dying is very difficult, and you'll have to do something completely absurd to die. Most of the riddles are straight forward and require logical thinking, and you'll manage to solve them without having to resort to walkthroughs. There are a couple of nice puzzles in the game, and they're challenging, yet not too difficult.

Two things caught my attention most. One, the voice acting. All of the dialogues in the game are voice acted, and it adds a new level of depth to the game- the player actually wants to hear all of the dialogues, rather than scrolling further.

The second thing is the magic system. Although you have a list of the spells, it's fun to build them yourself from the "runes" your character can use.

The Bad

The fans of the series will be disappointed from the transition. While the original characters remained, they have completely different roles, including the main character...

Somewhere in the middle of the game, one of the characters will reveal the entire plot to you. It's not very difficult to figure it out yourself, but silly to see the designers unfold the complete story in a couple of minutes.

The Bottom Line

Get it, play it. It's fun, easy and not frustrating like other adventure games.

DOS · by El-ad Amir (116) · 2001

Were this game a spiky club, I'd take up masochism

The Good

This game should be considered a classic. In fact, it's one of the most impeccably crafted games ever released, in any genre, in any decade, on any platform. The way it all comes together can just make you wonder sometimes why you even bother playing any other games - this game simply keeps on coming up with original scenes, with stunning plot revelations, with nearly metaphorical settings and with superb puzzles that are so deeply interwoven with the plot and the game world that you might not even realize that they are, in fact, puzzles. The game is quite lengthy yet there is hardly a single scene that could be classified as "filler" (to borrow a term from rock music criticism); there are so many different places, on several different worlds and "continents", yet at no point do you feel like a tourist being escorted through an art gallery at a rate of 5 paintings per minute just so you could say you've seen it all. On every world you arrive, within a couple of minutes you're immersed in the alternate, often somewhat surreal reality, fascinated by the rich imaginative atmosphere and puzzled by the complex of problems that gradually is revealed to you.

There's something fairy-tale about it all that charms and lends an easy-going air, yet almost at every step this lightness is matched by an undercurrent of graveness, sadness, despair, tragedy, and an epic struggle between some vague possibility of light and goodness and an overwhelming reality of evil and misery prevalent. This duplicity originates in the larger structure of the game itself: your grand quest to reunite the world and face the ultimate evil is given a "human dimension" by several excursions into the seperate parts of the sundered world, inhabited by races that have long lost sight of the "big picture" that is YOUR ultimate concern, and instead are occupied by their own internal struggles and conflicts. The effect of discovering such a self-contained universe with its own rules and power structures is surreal and fascinating; yet it is even more fascinating when you realize that their problems in fact have their roots in this same "big picture" that they all seem so painfully unaware of. It is indeed a rather philosophical metaphore, and it gives the game unprecedented depth.

You see, most plot-led games (yes, even "Grim Fandango") have just one single "context", or "plane" (in terms of plot construction only) - this game has THREE, namely the context of your quest to restore the world and battle the "ultimate evil" (the fire-breathing dragon thingie on the cover), the context of the lives and struggles of the races living in the 3 populated sundered "worlds", and the context of your own identity in the racial struggle between your race, the Patryns, and the race that imprisoned you 2000 years ago, the Sartan.

This last context is particularly interesting from a "literary" point of view, as it involves things like loyalty, forgiveness, moral decisions and betrayal, all brought to life without the usual excesses of soap opera a la Final Fantasy and suchlike Japanese cartoon crap. The literary qualities of the game are indeed high in all possible aspects - the conception of the world itself is quite individual and in fact originates from "philosophical circles" (however dubious they may be, this still sets the game apart from practically every single game out there), the language is vivid and precise and the plot is constructed with skill and imagination, using all the attention-grabbing and gasp-inducing mechanisms out there.

But the literary aspects aside, where the game shines most is the actual puzzle-solving element. That's right - a game with one of the greatest stories in computer gaming actually puts the focus on the gameplay. And what gameplay. Forget stupid use broom-stick with mouse-hole to awaken the cat to get the book he's lying on puzzles (gee, I should get LucasArts to employ me). In this game,

1) puzzles are there to achieve something important;

2) puzzles are logical and involve rational thinking, ie, thinking about what you NEED and how to get it, rather than about what CAN be done and what the designers could've expected you to do;

3) puzzles are fun and user-friendly.

I haven't read the book, and don't know anything about the authors' style of writing, but I have to tell you that I don't see how this sort of a story could've remotely worked in a book. Either the designer has totally done everything from virtually scratch, or the book is, er, "something else". This is perfect for an adventure game: people use spells on you, you learn them, use them yourself; people leave objects lying around, you pick them up and use them; people throw obstacles at you, you invent ways to surmount them. This does not make for extremely exciting reading but it makes for a very satisfying game, the sense of accomplishment and participation continually accompanying you. It's not much fun, however, to read about the accomplishments and survival/adaptation/development of others. But, then again, most fantasy novels are crap exactly because they talk on and on about the ingeniousness and accomplishments of others, so that might very well be the case with this game's origins.

And yeah, I did mention using spells. They kick ass. Check this out: possess the body of a dog, bring paintings to life, compete in magic with your mirror image, manipulate servile zombies, unravel magical illusions, pretend to be the death god of a bunch of tiger people, use magic to make statues walk, etc. Did Simon the "sorceror" ever do stuff like that? Pah.

The Bad

"Mensch"? No kidding. The "philosophical circles" I mentioned are in fact the circles of people like Ayn Rand and Nietzsche at his worst. The "mensch" races of humans, elves and dwarves are continuously referred to as some sort of lower beings, and the "moral attitude" towards them consists in being "nice" and "sympathetic" to them rather than enslaving them or "letting them kill each other". And you obviously belong to the higher, noble race of sorcerors and "leaders". What kind of escapist, megalomaniac bullshit is that.

As to the practical problems with the game, there are very few. The static first-person image on your screen, virtually devoid of any movement, does not help in creating an illusion of a living world. And the literary talents of the writer seem to have stopped at the point of diversifying the speech and writing styles of the many characters - they all talk the same, and even supposedly "scholarly" books (which are supposed to be "dry") occasionally start sounding like some fellow on the Usenet wrote them. There are also some minor issues with some spells just too obviously being provided to you just a couple of screens before you suddenly need them, and some people being jailed and given slow-acting poison literally hours before the same thing happens to you. That's forgivable. (As would be the occasionally confusing directions of the navigating compass, if I'd understand WHY - why does the arrow point left if I have to go straight forward? That's stupid.)

The Bottom Line

Come on. It's based on a best-selling fantasy novel written by two highly-regarded female authors. It's designed by a fellow who co-designed StarControl 3. It's developed by the same company that released Shannara only a year later. And given all this, it still manages to be awesomely good! What are the odds against that?

DOS · by Alex Man (31) · 2003

Trivia

Extras

Packaged with the game was an exclusive short story set in the Death Gate universe, by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman.

Graphics

The game includes two sets of artwork: a high resolution 640x480 SVGA version, and a low resolution 320x200 MCGA version. The graphics of the latter are not automatically scaled down from the SVGA version; they were manually redrawn to take advantage of the lower resolution.

Inspiration

Based on The Death Gate Cycle, a series of novels by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman.

Voice acting

Lead designer Glen Dahlgren provided the voice of Sang-Drax.

Information also contributed by Kamnari and Ye Old Infocomme Shoppe

Analytics

Upgrade to MobyPro to view research rankings!

Identifiers +

Contribute

Are you familiar with this game? Help document and preserve this entry in video game history! If your contribution is approved, you will earn points and be credited as a contributor.

Contributors to this Entry

Game added by Eurythmic.

Linux, Macintosh, Windows added by Cavalary.

Additional contributors: Patrick Bregger.

Game added July 21, 1999. Last modified February 20, 2024.