Braid

Description official descriptions

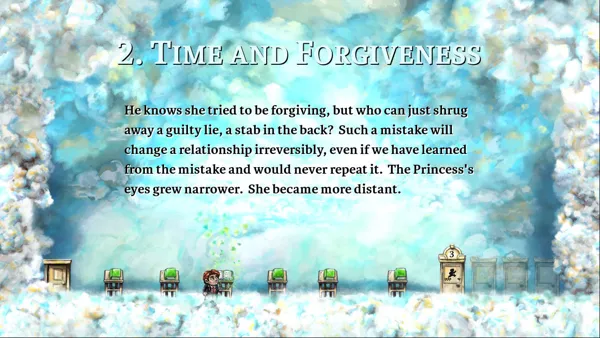

Braid is a puzzle game disguised as a 2D platformer. The player controls Tim during his search for a princess he has known and lost. Although the objective appears to be rather straightforward at first, the meaning and the motives become much more implicit and are interwoven with the mechanics during the course of the game. From the main hub, Tim can eventually access six worlds that consist of different areas. The start of each world reveals a part of Tim's background and emotions, rather than progressing a storyline. The second to the sixth world can be entirely explored without solving all the puzzles. Difficult situations can be ignored and revisited later. When all worlds have been completed, the first one becomes available and brings closure to the story.

The game's concept is entirely based on time manipulation. Tim cannot die permanently as the player can rewind time at any moment and usually for any length, even all the way back when an area was entered. While rewinding, the music is synchronized in a similar fashion. Rather than a gimmick, rewinding is an essential element to solve the puzzles. The different worlds give a spin to the mechanic by introducing clones as the player collaborates in a parallel reality with a past version of himself, time can be affected through the movement direction, and Tim can create a circular area to cause time dilation. Certain items, enemies, and parts of the scenery are immune to time manipulation or behave in a very different way. Puzzles require close examination of the environment and the behavior of different items and enemies. As such, the game is entirely about solving the puzzle theoretically by applying the game mechanics and then using trial and error to executive it and discover possible flaws in the proposed logic. This also brings limited replayability to the game.

A world is solved by collecting the puzzle pieces. These need to be arranged and eventually show a picture related to the game's story. There is no filler in the level design, meaning that every platform, item, or game element (except for a few enemies) has a specific purpose to solve a puzzle. Fast times can be tracked in a separate speedrun mode.

The later released Windows and Macintosh versions are identical but come with a level editor.

Spellings

- ブレイド - Japanese spelling

Groups +

Screenshots

Promos

Videos

Add Trailer or Gameplay Video +1 point

See any errors or missing info for this game?

You can submit a correction, contribute trivia, add to a game group, add a related site or alternate title.

Credits (Xbox 360 version)

86 People (77 developers, 9 thanks) · View all

| A Game by | |

| Graphic Art by | |

| Additional Graphical Effects Programming by | |

| Animation Prototyping by | |

| Additional Sound Effects by | |

| Helpful Patron | |

| XBLA Facilitation | |

| Room and Board | |

| Rewind Evangelist | |

| Play-Testing and Discussion | |

| Special Thanks | |

| [ full credits ] | |

Reviews

Critics

Average score: 92% (based on 75 ratings)

Players

Average score: 4.0 out of 5 (based on 141 ratings with 7 reviews)

The Good

The best a review for Braid can do is convince the tiny faction of players who shied away from the superficially simplistic platform style of the game to finally play it. Let me try that by dropping all the fake "objectivity" and be upfront about it: I adore this game. I wholeheartedly agree with its status as the most shining example for "games as art" and see no good reason for anyone to come to a different conclusion. I don't feel like a fanboy, either. It just comes naturally.

Braid is more than a jump & run. It is more than a puzzle game. Even more than a time-rewinding brain teaser. It is a milestone in its decade's game design and development process, the point where the hugely popular mainstream blockbusters and the innovative indie scene (that emerged out of the frustration about the bland landscape of mainstream gaming) merge into one of gaming's first, big "art game". Like a Darren Aronofsky film that, despite being far off the Hollywood mainstream, unites people who would normally never get close to that kind of film with the underground audience of movie-buffs. Simply because it is that good. There is no discussion about taste or personal preferences. Everybody can look at it and agree: If it's not to your taste it's worth changing your taste for it.

I could go on now and describe the artwork and sceneries that, thanks to a vivid use of particle effects and a structure that doesn't follow the boxy tile-set aesthetics of usual platformers, feel like a Van Gogh painting coming to life. I could praise the melancholic violin score that sets the mood and atmosphere so perfectly. I could try to explain the time-rewinding feature that turns this game from an ordinary platformer into an intelligent puzzle game. How it uses even the most obscure applications of the time-bending mechanics to squeeze every last drop of gameplay out of it. But it is all useless anyway, since not even a screenshots or video footage could explain what it feels like to play this game-- most importantly, to play it through. It's a ride.

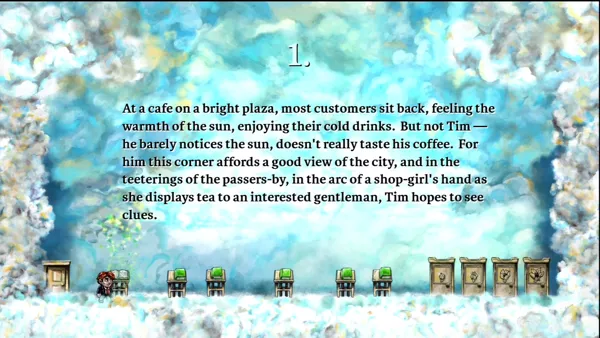

The cogs in your brain are running hot while trying to solve the most difficult puzzles, yet you can, literally, run through most levels without touching a thing. Time and chronology mean nothing. The game starts in chapter 2, ends in chapter 1, and that is only the easiest route. Just when you're exhausted of gaming-equivalents of Mensa-application tests, the game throws you in an empty room with a number of open books, each containing a passage of what reads like a novelized diary. Personal tales of leaving home, meeting a girl, success and failure. A reality check in a perfect fantasy, like a real-world slap in the face right in the middle of pure, escapist gaming bliss. Of course, the story doesn't come to a conclusion, starts to spin into a violent loop and, even beyond the finale, allows a million ways of interpretation. The game never makes it easier for the player than it absolutely has to, keeping you at your toes from the introduction to the end, somehow without ever getting frustrating.

The Bad

Are there things to criticize? Who am I to tell. I honestly think that Jonathan Blow knows more about what makes a game work than every game reviewer out there combined. Even the ones I like, whose blogs I read and whose opinion I usually value. They can't do more than give it a 10/10 and shake their heads in confusion about what they just experienced. And neither can I.

I can't even say that this would be "the best game" in any category. It isn't. Or at least it would feel cheesy to give it that title. Braid doesn't need that. It doesn't need top-10 or best-of lists. It's beyond that. Smaller, bigger... out of that loop.

The Bottom Line

It seems as if there is a new trend of rediscovering pure, unadulterated gameplay and using it as an inspiration for storytelling. The result is a symbiosis of the two rather than a two-pronged approach.

World of Goo, even Portal could fall into one category with Braid here. All are popular games that take a single idea, put it into a recursive loop until even the last bit of potential gameplay is discovered and then use the new-found gaming mechanics in a metaphorical way to embed them in a surreal story. A story that could not be told in any other medium, a wonderful world of meta: The sign painter in World of Goo, the training levels being turned into story elements in Portal and Braid's ponderings of rewinding time in the real world... it is a new, fresh pattern that rises out of the boring same-old in mainstream gaming and somehow manages to get wide-spread popularity and pop-culture appeal. You find Braid coverage next to Call of Duty 4 ads and previews of World of Warcraft expansion packs. And yet there is no way even the biggest studios out there could mimic this style by throwing expensive decoration on top of uninnovative gameplay.

Braid, for me, is like a "missing link" between mainstream and indie gaming, a chance for the independent to finally make a living and gather well-deserved respect from the masses. The game is just an example for a trend, but what a perfect example it is. If you call yourself a gamer there is no way around it.

Windows · by Lumpi (189) · 2010

The Good

Thinking about the moments I played Braid, mostly late at night, it brings back the range of emotions that went through me. In the dimly lit room, the game took me on a grand voyage of surprise, frustration, victory and sadness. It was a sensation I can only compare to some of the best titles I have played, such as Shadow of the Colossus, the first Monkey Island, Ecstatica or Dreamweb. A large part of my enjoyment of those is because they arrived at the right moment in my life and fit the way past games shaped me as a gamer and my expectations for new experiences. Braid is different however, as it has many layers you need to peel away at first. It is a game with many disguises and your enjoyment will depend on plunging through the different surfaces.

To understand why this game is so different, you need to know more about the author, Jonathan Blow. The past few years, he has been very vocal about the industry and trends, loathing design choices of heralded games such as Half-Life 2 and calling World of Warcraft a treadmill of tedium, a drug, the junk food of gaming. He labels the game "unethical", saying it provides simple rewards for a suffering scheme to keep players in front of their computers. Much as why I am drawn to indie games, he longs for the sense of wonder that pulled him in as a kid. But growing up, expectations change and he feels too few games manage to grow along with a maturing audience.

Secondly, he says games have to find their own voice, in the way music captures through sound, books through words and imagination, and movies through images. Too often games mimic tried concepts of other media. For games, this has to be the game mechanic itself, something inherent to the idea of a game. Blow also loathes cut-scenes as a way to tell a story, it should stem from the gameplay. In that way, Braid is not a game to attract a new audience, it's a gamers' game. While I expected a game such as Heavy Rain to take storytelling one step further, Blow does it through the age-old concept of a platformer. Yes, Braid is just a regular platform game, no different from Super Mario Bros. and nothing in the game design is particularly new. That means that with no instructions available, anyone knows instinctively how to play. You walk, you jump, that's all there is. While exploring the worlds however, accessed through the protagonist's house, further game mechanics are discovered rather accidentally with small hints. You find out you can rewind time, retracing every step you have taken in a level and back as far as you want. Each world uses a variant of time manipulation. The way time is manipulated does not become increasingly complex and difficult. In some worlds you reverse time (and as such you can never die), in others time changes according to your movement, you collaborate with a past version of yourself in a parallel reality or slow down time in a specific area. The platforming is eventually a false sense of familiarity, as Blow uses it as a vehicle to tell his story, twisting the genre into unexplored paths. It does not even matter if you like platformers.

Time manipulation is the only mechanic you need to learn and you use it solve puzzles. Certain objects and items are affected differently through time and you need to distort reality to turn it to your advantage. Almost all worlds can be travelled right away. There are no enemies you absolutely need to kill, you can just walk straight through a world and decide to finish it later, a very meditative experience. Each world holds a number of puzzle pieces that need to be collected and arranged into a frame to reveal a photo. The story about Tim's seemingly simple quest for a princess is carefully mixed into the gameplay, even though Tim never speaks and does not meet anyone directly relevant to the story. He is also very out of place, a tiny man in a suit with his hair neatly brushed in a fantasy world, but this is for the player to discover. The way time is manipulated and puzzles are solved is a part of the storyline itself. Before attempting to grab a puzzle piece, you need to examine the behaviour of enemies and items, imagine how your time manipulation can affect them and devise a strategy. Mostly, you will be solving puzzles by devising a pattern in your mind before even trying. If it does not work, you rewind time, look where you went wrong and adapt your strategy. The puzzle pieces that form pictures resemble Tim pondering his past, trying to fit the pieces. Final clues to the story are provided through a few sentences at the beginning of a world. Very little is revealed and the search for the princess soon becomes a metaphorical quest for something completely different. Like a poem, with so little details, it is profound and deeply moving, yet largely implicit and asks the player to work it out himself. Even more, you can easily ignore the entire story as there are no sequences where you are forced to read or interpret, it is entirely optional. But when you do get to the final world however, the mixed and reversed storytelling leads to a tremendously powerful ending where everything you thought you knew is brought into a very surprising perspective you could not possibly imagine.

The gaming roots also show. The end of a level, “The princess is in another castle”, a sentence burned into the collective gaming history, is given an entirely different meaning in this game. The cheerful graphics will deceive the player how much of a melancholic reminiscing about regret it is, though it is open for interpretation.

The quiet atmosphere is enhanced through fitting music and beautifully drawn graphics. They complement and dearly need each other. The way rewinding time is reflected in visuals and music is stunning. There is also no filler. All puzzles and scenery have a meaning in the game. Even though it can be considered quite short, none of the gameplay seems abundant or meaningless, everything is moulded together with mathematical precision. After finishing the first five worlds, a ladder can be constructed to the attic in the house where a final world brings closure to the story. It is not told in a linear way however. Each sequence reconstructs another memory and your insight into the events constantly needs to be adjusted. Many of the puzzles seem very difficult at first, but there is always a logical solution. They are hardly ever the same and the ingenuity of some will leave you baffled. When you finally figure it out, you feel a great and deserved sense of accomplishment.

The Bad

It is not a game for everyone. If you cling to a certain genre Braid can be disappointing. There is no action without meaning, no dying, and no enemies to defeat without a purpose. You can finish a level without any action at all. Without the background story, as faint as it may seem, this game would not make sense. If you don't grasp all the elements that make up the game world, it doesn't work. On paper it seems poor game design, but Blow is incredibly clever in his presentation. You grow along with the game and it is hard not to be impressed by the maturity carefully crafted into the game design when it fully reveals itself. This game is however a must for anyone who has been playing for many years, as a mosaic that brings together some of the best elements from gaming history (hence the title) with fresh ideas.

The Bottom Line

Braid is a one-of-a-kind experience, a game stronger than anything else released before, because it is not ashamed of being a simple game at the surface. It acknowledges everything that precedes it, but refuses to be influenced by other types of culture. As Blow once said, there will eventually be games you cannot explain or compare. You simply need to have played them to know what they are. Through the humble, yet familiar game mechanics, Braid tells a story that puts almost everything on this site to shame. When it finally comes to full bloom in the end, it stands tall as a masterpiece that mocks every revolution the game industry has been preaching. As such it deserves my humble praise and a hearty recommendation.

Xbox 360 · by Sciere (930794) · 2009

Poor puzzles, poor story and poor references, but hey, it's artsy so we have to like it.

The Good

The backgrounds in this game are very beautiful, every single one of them is hand-drawn and the aesthetic is very original. Braid focuses mostly on looking beautiful and I'll be damned if it doesn't pull that off very well. The art-style for the backgrounds also fits really well with the level-design and the style is consistently present, while also varying enough to stay interesting.

Likewise, the spriting is also done very excellently. I want you to jump on one of the basic enemies and then slowly reverse time, you will see the expression on the sprite change slowly instead of an instant-transition, that's pretty cool. Like with the backgrounds, the sprites fit really well with the overall aesthetic and this all creates a sense of atmosphere that I personally found quite endearing.

Like with "Banjo & Tooie" this game has you assembling puzzles, this time around in order to finish a level off entirely. I actually really enjoy this, I like making puzzles and when done virtually I don't end up with a million boxes and missing pieces.

The Bad

The story in this game is very poorly implemented, to the point of it been a few steps back in video game storytelling. Remember how I said that in "Bastion" the gameplay and story are perfectly put together? Braid does the complete opposite and gameplay and story are kept miles away from each other. Before you start each level there are a few books on pedestals that you can read, each containing an entire paragraph of ambiguous text that is supposed to form the story. Some call this poetry, but I call it retarded. I am not saying that a 2D platformer can't have a story, but when we have to go out of our way to read a load of text before we get to play, then that is clearly a failure. As for the content: I am underwhelmed. Every level just turns around the same thing: Tim is a whiny idiot, he is looking for a princess and the game can't go for a single level without referencing the atomic bomb.

On the gameplay side of things there is nothing groundbreaking to be found either, in fact, the gameplay feels very out of place. The story and atmosphere set the game up as a very dark or at least a dramatic experience, but once gameplay starts you are jumping around with cute creatures while cheerful music plays in the background. At first glance the first level appears to be doing a Mario reference, but you quickly realize that the entire game is a Mario reference. Every single level uses the piranha plants coming out of green pipes, goomba-like enemies walking straightforward until they hit something and weird-looking creatures at the end of levels telling you the princess is somewhere else. The entire game is like this, so I consider myself justified in saying that it's just Super Mario with puzzles and artsy bullcrap thrown into the mix.

Unlike what the creators claim, the puzzles in this game border on the horrendous. Their official strategy guide says that all the puzzles are fair and never involve guessing, but in the very first level I was confronted with a puzzle that demanded that I grew bored and started fucking around with the scenery (turned out you could move the picture frame, thanks for hinting at that, that clearly didn't leave me guessing for random solutions). There are plenty of examples all around and one of the most mind-bending of them is a puzzle where there are two doors and only one key, one door opens and the other breaks the key and forces you to repeat the entire stage. That is a returning puzzle, ladies and gentlemen!

In fact, there are quite a lot of stages that demand you reset everything if you make even one mistake. One annoying example was early on in a level where certain elements were immune to your time-reversing abilities. The only puzzle here was that two platforms were moving towards each other at exactly the right timing, but one was immune and the other wasn't, so in order to prevent a conflict I just had to wait... next to three enemies with varying attack patterns.

Also unfair about the puzzles is that they are incredibly overwhelming. Many stages contain various dynamic objects that start working the second you enter, this creates the problem that the player can never get his bearings before diving into the actual puzzle. Imagine if you're playing Banjo & Kazooie and once you enter Mumbo's mountain you don't start off on top of that hill without enemies, but next to that monkey throwing fruit at you and with no way to escape. As the game is normally, you can observe the monkey from a distance, but in this scenario (which is what Braid does) you are just going to run around in circles because you can't grasp what is happening around you. What Braid does can be done right, like in Ocarina of Time where you enter that icy room with the timer, it gives you a quick adrenaline-kick and forces you to think faster than usual, but when the entire game is like that...

The Bottom Line

Many people praise Braid because it shows that "games are mature" and "games are art", but personally I can only see a poorly-assembled mess of a game. I do believe that some games are mature and I most certainly believe that games art, however I also believe that you don't need to throw in pointless references or ambiguous paragraphs of text to achieve it. I think Bastion is a piece of art, the same can be said about The Path, "art" is not some kind of official stamp that government employees hold meetings over, it's an opinion that varies from person to person. I think Psychonauts is a piece of art, but on the other side I don't care for modern paintings.

If you hang out on websites like The Escapist were any game that a reviewer calls art is immediately consider to be 100% flawless, then this title should definitely be on your to-play list. Besides that, I can only recommend this game to the so-called "hipsters".

Windows · by Asinine (956) · 2012

Discussion

| Subject | By | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Recommended literature | Sciere (930795) | Sep 7, 2008 |

Trivia

1001 Video Games

Braid appears in the book 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die by General Editor Tony Mott.

Budget

Developer Jonathan Blow said he invested about $180,000 of his own money in a three year period to create the game.

Inspiration

In an interview with the website Joystiq on 25th September 2008 Jonathan Blow cites the musical influences that initially lived in the same emotional neighborhood as Braid: the album Horse Stories by Dirty Three, the music of Lisa Gerrard, and the soundtrack to Dead Man by Neil Young.

References

Many of Braid's levels appear to draw their names from various cultural sources: level 3.2 -- There and Back Again -- is from fictitious hobbit Bilbo Baggins' autobiographical account of his adventures in author J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit, while level 3.4 -- The Ground Beneath Her Feet -- is named either after a book of the same name by author Salman Rushdie or the U2 song also inspired by the book. Level 3.6 -- Irreversible -- suspiciously shares a title with a French film told employing an unorthodox time flow, while levels 4.2 -- Jumpman -- and 6.6 -- Elevator Action -- are names of video games. (Level 6.7 -- In Another Castle -- is one of many nods this game plays to the great granddaddy of the platform genre, Super Mario Bros.)

Awards

- GameShark

- 2009 - Best Xbox Live Arcade Game

- GameSpy

- 2008 – XBLA Game of the Year

- IGN

- 2009 - Overall Best Puzzle Game

- 2009 - Best PS3 Puzzle Game

- 2009 - Best PC Puzzle Game

Information also contributed by Big John WV and Sciere

Analytics

Upgrade to MobyPro to view research rankings!

Related Sites +

-

Braid

Official game website -

Braid

TIGdb entry. -

Mac Gamer Review

A review of Braid by the Mac Gamer's Brad Snios, who had a generally favorable outlook on the game and its nature as a port (July 17th, 2009). -

Podtoid 66: Braidtoid

A podcast with Jonathan Blow about the game design, hosted on Destructoid (21st August 2008) -

The Art Of Braid: Creating A Visual Identity For An Unusual Game

Artist David Hellman explains his collaboration with Jonathan Blow to create the art for the game, on Gamasutra (5th August 2008) -

The aesthetics of puzzle game design — A good puzzle game is hard to build

Interview on puzzle game design to Jonathan Blow, author of Braid, along with Sokobond's Alan Hazelden, and Jonathan Whiting, co-author of Traal. -

Wikipedia: Braid

article in the open encyclopedia about the game -

X360A achievement guide

X360A's achievement guide for Braid.

Identifiers +

Contribute

Are you familiar with this game? Help document and preserve this entry in video game history! If your contribution is approved, you will earn points and be credited as a contributor.

Contributors to this Entry

Game added by Sciere.

PlayStation 3 added by Kaminari. OnLive added by firefang9212. Linux added by Iggi. Xbox One added by MAT.

Additional contributors: Kabushi, Pseudo_Intellectual, Solid Flamingo, Zeppin, Patrick Bregger, Starbuck the Third, FatherJack, Kennyannydenny, click here to win an iPhone9SSSS.

Game added August 8, 2008. Last modified March 31, 2024.